Writing a Will is one of the single most important things we can do in our lifetime. It’s a reflection of the people we care for and the causes we believe in. At The University of Manchester, we owe our very existence to gifts in Wills. And one remarkable gift in particular paved the way for 5 Nobel laureates and some extraordinary scientific discoveries.

Five Nobel Prizes for £10,000 - an extraordinary Manchester story Share on X Updating your Will? Find out the incredible impact your gift could have at Manchester Share on X What could you achieve through a gift in your Will? Share on XFor anyone who has visited The University of Manchester and marvelled at its iconic buildings, it’s hard not to be impressed by the beautiful architecture. The imposing Whitworth Hall, the neogothic John Rylands Library and the stunning Christie Building are just some of the historic landmarks made possible thanks to the generosity and vision of a handful of men and women in the 19th century.

Many of these Victorian philanthropists are well known to students and staff on campus – their names visibly carved out in stone, adorning our historic buildings. Whether you enjoy a coffee in the Christie Bistro or graduate in the Whitworth Hall, the legacies of these people are hard to miss.

At The University of Manchester, we owe our very existence to gifts in Wills.

A lesser-known name

Yet one name in particular might not stand out so visibly: that of Edward Langworthy. And despite his legacy being just as important as any donor, his name is not given to any building, library or museum. Instead, his legacy is a single Professorial Chair in Experimental Physics, which has become one of the most remarkable stories in the University’s history.

Born in 1797, Langworthy was a successful businessman and Liberal politician. Initially from London, he moved to Salford in 1840 at the height of the industrial revolution. Capitalising on Manchester’s booming cotton industry, he set up a cotton mill, Langworthy Brothers and Company. By 1848, he was elected mayor, a position he held until 1850.

During his time as Mayor, Langworthy’s commitment to improving public good shone through. He set up the first free public museum in the county, and later set up the first free public library.

On his death in 1874, Langworthy, by this time a wealthy man, left a generous £10,000 bequest in his Will to one of the University’s predecessor institutions, Owens College. His vision for his legacy was crystal clear: “It being my wish that students may be instructed in the method of experiment and research and that science may be advanced by original investigation.”

The first Nobel Prize

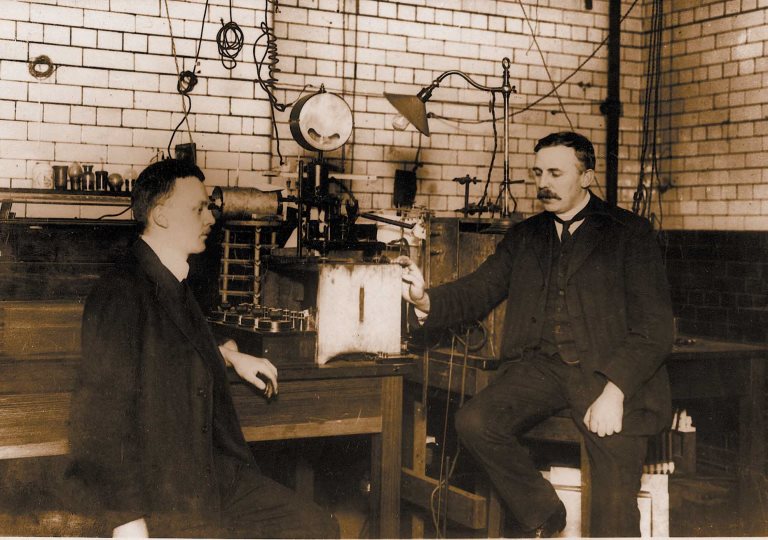

This £10,000 endowment, worth around £850,000 in today’s money, was used to establish the Langworthy Professorship in Experimental Physics. Within a single generation the professorship had borne its first Nobel laureate, with Ernest Rutherford winning the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1908.

Rutherford’s career as a researcher was the perfect embodiment of Langworthy’s commitment to supporting new discovery. In 1919, Rutherford transformed nitrogen into oxygen, the first successful transformation of one element into another, and in 1932, he was successful in splitting the atom for the first time. A true pioneer, Rutherford fundamentally changed the way we viewed the world.

Continued success

40 years after Rutherford’s Nobel Prize, the Langworthy Professorship had produced another two laureates. In 1915, William Lawrence Bragg became the youngest ever Nobel laureate at 25, winning the Nobel Prize for Physics alongside his father for ‘services in the analysis of crystal structure by means of X-ray’.

Patrick Maynard Stuart Blackett became the third holder of the Langworthy Professorship to win a Nobel Prize. His work looking at the tracks of atomic nuclear disintegration earned him the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1948.

Langworthy’s legacy today

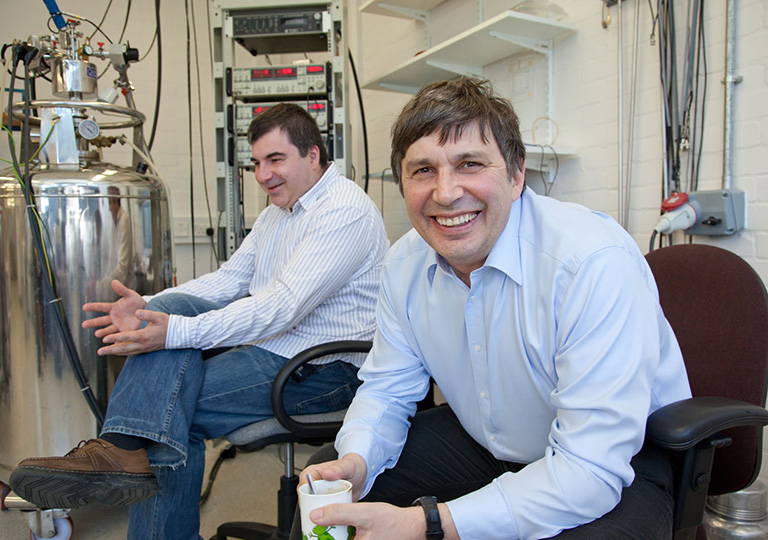

The next two winners both came in 2010, when Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov won the Nobel Prize for Physics for their ground-breaking discovery of graphene. Geim was the Langworthy Chair at the time of the Nobel Prize, with Novoselov taking over in 2013.

The work of Geim and Novoselov and the discovery of graphene is the perfect testament to Langworthy’s original vision of supporting experimental physics and advancing human knowledge when he left his gift to Manchester. The impact this wonder material will have on the world is not yet fully clear, but it is already showing huge promise in a whole range of areas, from charging phone batteries in five seconds and treating osteoarthritis to desalinating sea water and creating low energy lightbulbs.

The University of Manchester has produced 25 Nobel Prize winners over its rich and illustrious history. With five so far holding the position of Langworthy Professor in Experimental Physics, who knows what the next holders of the Langworthy Professorship will achieve? One thing is clear, five Nobel Prizes for a gift of £10,000 is quite an investment.